An interview with Mattias Berg, author of THE CARRIER

On the day we publish The Carrier, we are delighted to bring you this interview with Mattias Berg, discussing the book, his inspirations and the many issues raised by this highly original thriller.

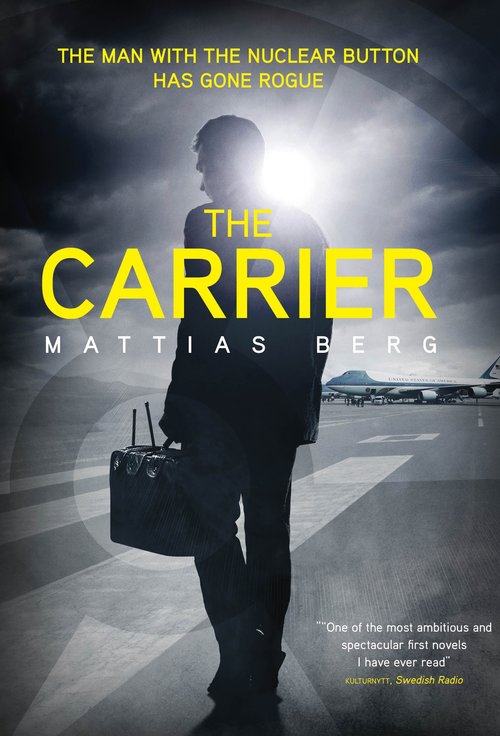

The Carrier is now available in all good bookshops, translated from the Swedish by George Goulding.

1. What was the initial inspiration for The Carrier?

When Barack Obama came to Sweden in 2013 – the first official visit ever of an American president – I walked through an abandoned Stockholm. The entire city centre had been cleared for security reasons.

There was such a strange atmosphere, silent and hollow, reminding me of the primal fear from my youth: that an atomic bomb had struck somewhere nearby, killing most of us by radiation.

During the sleepless night that followed, I went through the media reports about the President’s vast retinue. And then I realised that the man with the nuclear briefcase was still there. He who had the codes that could set our world on fire. Last seen in books and films during the late 80s, before the end of the Cold War, as a popular cultural cliché.

Soon I was researching more professionally, during my spare time but as the journalist I have been for 35 years now. I learned that this man had been standing at the American President’s side ever since the beginning of the 1960s. Even when Obama received his Nobel Peace Prize 2013 – largely for a famous speech against nuclear weapons.

And the more I read, the less astonished I was at that man’s presence here in Sweden. Because the world’s nuclear arsenals had not faded into the background – as I and most of us had thought – but were rather undergoing rapid expansion.

In the U.S., the cost of what is often referred to as “The Revitalization” of its nuclear weapons systems is currently estimated at almost ₤400 billion over the coming decade alone. In Britain, the Trident replacement could have a lifetime cost of around ₤200 billion.

A month after the man with the nuclear briefcase had visited Stockholm, I started sketching his story.

I tried to imagine who he actually could be. How a single human could cope with having the apocalypse – triggering it, or preventing it, or just carrying it around – as part of his daily routine. And what would happen if this key figure defected, for one reason or another.

This was the initial inspiration for what eventually became my suspense novel “The Carrier”. With the actual facts of this incredible human endeavour, our most ingenious invention, a tool for destroying ourselves, laying the groundwork for a fictitious plot. And with the man with the nuclear briefcase as a first person narrator.

Revealing everything, in his own words, about his role – and his impossible escape from its responsibilities.

2. As a journalist, were you never tempted to write a non-fiction book on the topic of nuclear weapons instead?

Yes, I must admit that after learning about the man with the briefcase and the current expansion of the global nuclear weapons system, that was my first thought.

In the 1990s, I wrote a couple of non-fiction books on what in many ways is the overall topic here too: the relationship between technology and culture. The first book was about the dawning Japanese information society and its links to the country’s ancient traditions, and the second was about the cloned sheep Dolly and the emerging biotech industry’s dream of creating new life.

But as I delved deeper into my research about nuclear weapons, I became convinced that this time it had to be fiction. Partly because I hoped to spread all this terrifying knowledge to a broader, perhaps international audience. Partly, and indeed for the most part, because so much to do with nuclear weapons in itself eclipses reality. From the very start, when we actually created a tool for destroying ourselves – to the current situation, when we “revitalize” this doomsday system at an unfathomable cost.

As with my books on the information society and cloning, though, I needed to put this high technology in a wider context. Embed it in psychology, philosophy, art history; try to understand our breeding and nurturing of this demon outside and inside ourselves. Its incomparable threats and temptations.

This is why The Carrier does not play out in the same way as many other suspense stories. Why I rather tried to let it fold and unfold, revealing hidden pockets and compartments – like the enigmatic bag Jesus Maria crafts for Erasmus in the novel.

3. At what point did you decide that the story of Lise Meitner would be important to the novel?

Some rainy day during my intense research – a cultural journalist slowly becoming something of an “expert” in nuclear weapons – I learned that the world’s most renowned nuclear physicist fled to Stockholm just before World War Two. Although Lise Meitner remained here for more than two decades, very little is known of what this Austrian-born researcher of Jewish origins actually was doing here.

The more I read about her, the more fascinating and bewildering she seemed. She declined to join her famous international colleagues in their quest for the atomic bomb in Los Alamos, but instead worked with the experimental reactor R1 in Stockholm: the starting point for the Swedish nuclear weapons programme.

After the war, Lise Meitner was offered a prestigious guest lecture post in the U.S., and dubbed “The Mother of the Atomic bomb” in the media as well as “Woman of the Year”. But she chose instead to return to her seemingly insignificant research in Stockholm, becoming a Swedish citizen in 1949 and eventually moving to join relatives in Oxford in 1960.

So that is why I decided to incorporate what I in my novel call Lise Meitner’s secret as one of the key plot lines.

Because this amazing researcher seems to embody humanity’s ambiguity towards our ultimate invention: nuclear weapons. And because her elusive life story was impossible to resist.

4. Could you explain the original Swedish title, The Triumph of Death (Dödens Triumf)?

There is a famous painting by the Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder with that title. I had seen it many times, but when I started writing The Carrier I really saw it.

His strange vision of the future, all the way from his time in the 16th Century to ours: such an exact way of picturing the nuclear apocalypse. All these corpses and skeletons all over the painting. The yellowish tone covering the entire burnt-out landscape.

Bruegel’s painting was inspired by the plague that devastated Europe towards the end of the Middle Ages, which according to many sources also inspired its title: “The Triumph of Death”.

The moment I came across that painting again, during the first period of researching, I knew I would use it in some way in my novel. Then I learned that the small town of Brogel in Belgium, which some researchers point out as Pieter Bruegel’s birthplace – with a museum that has copies of all his works – also hosts one of Europe’s most important nuclear weapons bases, Kleine Brogel.

So here was the connection, factual and fictitious. Bruegel’s painting gave me the possibility of setting nuclear weapons in a new context. Weighing them alongside other great human endeavours, using my professional knowledge as a cultural critic. Making the Carrier, Erasmus, the main character and first person narrator, as fascinated by mankind’s masterpieces throughout history as I am myself.

Both he and I trying – desperately – to grasp why as a species we put our inventive talent towards creating a tool for destroying ourselves. The Triumph of Death.

5. Do the facilities beneath Stockholm described in the novel really exist? What about the Swedish nuclear weapons programme?

Let me begin like this: A month ago I finally entered the most sacred site of the buried Swedish nuclear weapons programme, the tomb itself so to speak. The enormous hall blasted out of the bedrock of central Stockholm, deep down under the Royal Institute of Technology, once housed the experimental nuclear reactor R1. Now there was a dark hole where the giant apparatus stood, having finally been removed sometime during the 80’s.

This Saturday afternoon there was a screening of a French silent movie from 1956, accompanied by live organ music, in what now is called The Reactor Hall. During the movie I was furtively glancing at the small offices arranged against the steep rock wall behind us. Wondering which one was Lise Meitner’s. What she actually could have been doing in there, at the same time the film was being made.

So the answer is that there was indeed an ambitious nuclear weapons programme in Sweden too, with this reactor as the starting point for our efforts to build a bomb and Lise Meitner as some kind of jewel in the bedrock. Work continued fruitlessly behind the scenes through the 50s and 60s, before the project was quietly shelved for complicated political reasons. Sweden instead became a superpower in the cause of disarmament, with our nuclear weapons program not revealed until in the mid 80s when a technical magazine ran an expose.

After the Reactor hall was built during the 50s, we continued with what at the time was one of world’s largest nuclear shelters in the centre of Stockholm, Klara Skyddsrum, as well as a huge system of tunnels deep down under the capital – including the area where the tube station Kungsträdgården now lies and the escape during the first chapter of The Carrier takes place.

Furthermore, the suburb of Ursvik where Sixten and Aina live in my novel was at the very centre of Sweden’s nuclear weapons programme, the site of numerous offices and laboratories. And then we also had what was called “our Los Alamos” at Grindsjön just south of Stockholm, where the Swedish National Defence Research Organization (nowadays called FOI) still have an experimental ground.

Many of the facilities in The Carrier do really exist, and there are others that did not make their way into the novel, like Grindsjön. But the scale of the system of the shelters and tunnels under Stockholm, the entire Inner Circle, is a product of the author’s imagination.

6. Do you believe that the temptation to use nuclear weapons will eventually prove too strong for humanity to resist? From which simmering conflict do you think the flashpoint is most likely to originate?

These questions are too complicated and terrifying to tackle in this limited space! The Carrier can be considered a lengthy response to the first of them . . .

But let me say that we must not lose sight of the fact that we only have had access to nuclear weapons for less than 75 of mankind’s 300 000 years on earth. Which indicates that we still do not have any kind of “answer” as to whether the current strategy of deterrence practised by the super powers could be successful, or not, in the long run.

What many people tend to overlook, even in political circles, is that we today have thermonuclear weapons, fusion bombs, with far greater explosive power than the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even after decades of diminishing arsenals, there are still some 15,000 nuclear weapons between Russia and the U.S. alone. Thousands of them are on so called “Hair-trigger alert”, ready to be launched by a sudden decision of a single military commander – not just the President himself – and are capable of destroying a large part of our world within minutes.

Current theories also indicate that a full-scale nuclear war between Russia and the U.S. would result in Nuclear Winter, a rapid climate change event causing global starvation and – in a decade or so – total apocalypse for mankind. And that even a more limited conflict, say between India and Pakistan, would have grave effects on the long-scale ability of the earth to sustain human life.

And, of course, the threat could derive from one or a handful of individuals – as the plot in The Carrier indicates.

So, my answer about the possibility of a nuclear war might be that it is a psychological and philosophical question, just as much as a political one. Concerning the very core of ourselves, our long-ranging ability to withstand the darker aspects of our personalities. Comprising everything it means to be a human.

7. Or do you think there is the possibility of disarmament?

In The Carrier a kind of “quick-fix” for global disarmament is central to the plot. And I must say this fictitious method of mine, at the moment, does not really seem less credible than any other. Even though the disarmament organization ICAN got the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, not any of the nuclear countries – including Britain – seem at all willing to sign the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that has passed the General Assembly.

So we still have a very long road to take.

8. Given the importance of the nuclear weapons issue, why do you think it is so little discussed?

Primarily because we cannot not see any plausible solution to the problem. Once we invented these weapons we opened Pandora ’s Box and we do not know how to close it again. This is a great difference compared to the similarly crucial issue of climate change, which is at last beginning to receive the necessary global attention. There we can after all see some sort of solution, involving ourselves and choices in our daily lives – a link between what we do and what happens to the world.

But the silence surrounding nuclear weapons is also, I think, due to the fact that we do not really have the strength to imagine their potential consequences. That they really could send us all into oblivion within minutes. More or less for no reason at all.

9. Could you explain the role that cosmetic surgery plays in The Carrier?

Firstly, it is my own little tribute to Mission Impossible. Quite in line with the plot and Erasmus and his team’s so very secretive existence.

But more symbolically, the surgery and identity transformations indicate that the individuals guarding the most dangerous weapons in human history – the monster in mankind’s cellar – could be any one of us. Or rather: all of us.

10. Do you have a favourite character of those you created for The Carrier?

I have to say Ingrid, the mentor and the supervisor of Erasmus, The Carrier. His riddling cicerone initiating him into the underworld, and perhaps the real main character in my novel.

Amba, Erasmus’ wife, “the abandoned”, also continues to fascinate me. I am still not really sure who she is and what she actually knows about him. But it is so interesting that people with these kind of assignments – like carrying the apocalypse around, as Erasmus does – manage to have close relationships.

Maybe I will have to write a sequel to find out more about Amba. Her inner thoughts, emotions and plans.

11. Do you think that there is a further story to be told about any of its characters, or will your next book be completely different?

As I just said, I am tempted find out more about Amba. And I am also interested in taking the story from 2013 – when I started writing the Swedish version of The Carrier (“Dödens Triumf”) – to the present, with nuclear weapons once again so topical.

But at the moment I am finishing a totally different project. A historical novel concerning the relation between the two most dedicated female museum collectors ever. Something more in line with my profession as a cultural journalist. But still with a related theme of time, loss and eternity.

12. You wrote the novel in a pre-Trump world. Do you think it would be any different if you had started writing it after he was elected?

After the election of Trump, the super powers withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and North Korea’s missile tests, the nuclear weapons issue has of course come higher up on the international agenda (although it is still barely discussed in the Swedish media).

But, as Erasmus argues in The Carrier, the nuclear weapons system forms a kind of regime in itself. Its immanent needs, more than mankind’s, has for instance lead to the development of the entire space programme – to enable us to send missiles to other continents. As well as the whole computing industry, to control and command this our ultimate tool.

So even if Trump seems to be a more unpredictable president than many of his foregoers, there are so many other variables in this issue. The so called “Revitalization” of the nuclear weapons system was actually announced during the Obama administration. The very existence of this doomsday machine puts our entire civilization in sort of a half-way house. Between peace and war, everyday life and the apocalypse.

13. Were you inspired by any particular writers in the thriller genre?

Two masters, whom I read over and over while writing: the Italian Umberto Eco – most famous for his philosophical crime story The Name of the Rose – and the Danish writer Peter Hoeg. Especially his Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow, which offers a brilliant combination of depth and suspense.

14. If your book was an animal, what animal would it be?

Let me choose the Chimera. An ancient Greek mythological creature, which was a blend of different animals: often depicted as a lion crossed with a snake and a goat. In a similar way, I would categorize The Carrier as a hybrid between a thriller, an essay and a mystery.